Appearance

In the early spring of 2024, I was approached about consulting for a farmer-led software project called Farm Flow. At first, I viewed the project the way a software generalist and independent contractor would. I consciously guarded myself against becoming the proverbial "hammer that sees every problem as a nail" – that is, I did not want to force Farm Flow into Runrig's model for software design. I said as much to the software's creator, Matthew Fitzgerald of Fitzgerald Organics, on multiple occasions throughout the course of our early evaluation. It was no accident, however, that the project's underlying requirements and ultimate goals brought it into close alignment with my own stated objectives for Runrig. I was introduced to Matthew through Samuel Oslund of the 11th Hour Project, and no doubt Sam discerned the affinity between our two projects far more readily than I had.[1]

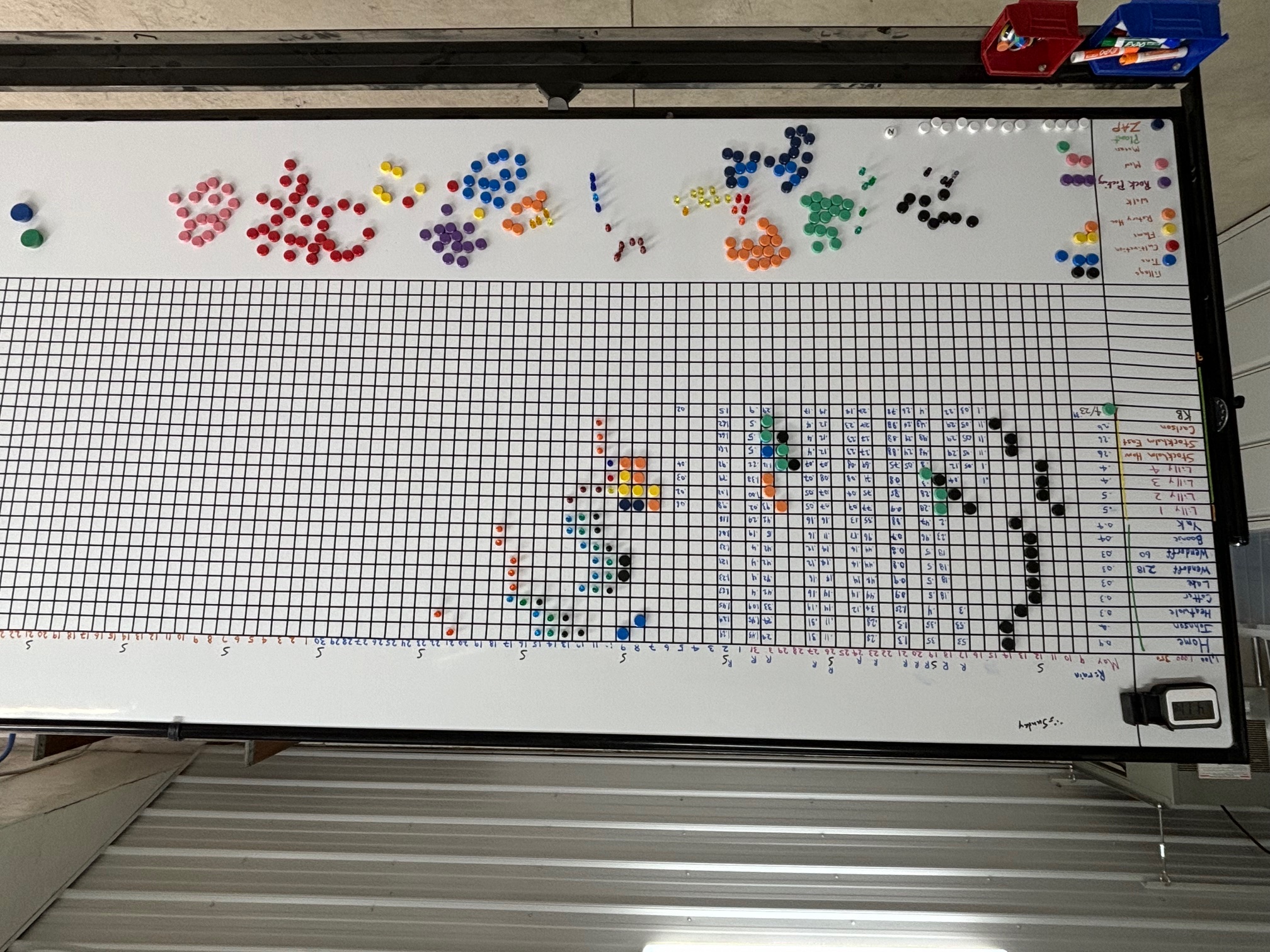

The Original Farm Flow Board

Farm Flow's first implementation was in physical form, which was a credit to the soundness of its design, by my estimate, since it had already demonstrated its effectiveness before any attempt was made to digitize it. I took it to be a positive indicator for its potential as a software project, too, so long as a compelling case could be made for how that might improve upon the physical design or introduce new affordances.

The physical implementation was a large whiteboard standing roughly 72" wide x 48" high in Matthew's equipment hangar. It was prepared with a grid of about 80 columns by 20 rows, give or take, meticulously etched out in black permanent marker. The grid represented the farm's entire growing season of planned field actions, with a column for every calendar day and a row for every field or planting location. The dates and location names were written in magic marker along the top and left-hand edges, respectively, so that the grid contents could be erased and reassigned with each new season.

Multi-colored magnetic discs populated the grid cells at various intervals, demonstrating some rather striking patterns, though their precise meaning was not immediately clear to the untrained eye. The rightmost extent of these discs – i.e., the column corresponding to the current date – was hemmed in by an array of magnetic pins, mimicking pushpin thumb-tacks in size and shape. The pins were similarly colored as the discs but translucent and about half their radius, so they stood out less prominently than the discs. The pins represented actions that were still only planned, while the discs represented those already completed. On closer inspection, some discs were even stacked upon others within a single grid cell; clearly some actions, if not all, could be performed on the same day in the same location, conditions permitting. In the wide open space below the grid was a hand-written legend indicating the name of the specific field action each color represented, alongside a collection of unused discs and pins clustered by color.

Some of the columns were occupied by a line of numbers, one or two digits faintly inscribed with a blue magic marker in each of the grid cells. These indicated rainfall amounts in decimal inches. They rarely coincided with any placed discs, since the actions they would have represented were prohibited by the rain (sometimes for several days following, too). The rainfall quantities varied in magnitude as they ran up and down the column, though only gradually, since the rows representing geographic locations on the farm were grouped by proximity.

The key to the whole enterprise was that there was nothing at all arbitrary in the arrangement of these field actions. Their precise timing and sequence were determined by a set of standard operating procedures, or SOPs, which were the product of ongoing development by this small team of farmers. The SOPs lived in written form within folders filed into separate trays that hung from the back of the whiteboard itself. The trays also held carbon-copy ticket books, which would be filled out with specific quantities and target values to inform the execution of a given operation at a particular time and place. Space was left on each ticket for the entry of actual values achieved or observed, so that upon completion the ticket could be stored in the appropriate folder for future reference.

That's the best synopsis I can give in just two paragraphs and it woefully oversimplifies the system as Matthew conceived it prior to my involvement. For more details, he gave an excellent presentation on Farm Flow to the OpenTEAM HCD Working Group in 2024 that covers the data analysis and layout of the board.

A Previous Attempt

Prior to our introduction, Matthew had commissioned another software team through Upwork. They produced a fairly generic client-server web application, with an SQL database and multi-user access control, plus an iOS app with basic form views for updating the activities and locations. The web dashboard offered several visualizations of the farm locations and activities, but these didn't correspond at all to the unique visual language of the original whiteboard, nor did it capture or display the most critical datapoints and processes in the SOPs.

This initial prototype was far from a trivial accomplishment; even as typical as those features are, they still entail plenty of complexity to develop and deploy, which I certainly do appreciate. It's also hard to conceive of a final version of Farm Flow that would not require similar functionality for network connectivity, remote persistence, multi-device access, and permission-based collaboration; outside of those typical requirements, however, the application achieved none of what actually makes Farm Flow unique. In the end, nothing from that effort proved salvageable, since communication with their team was always intermittent at best and the source code was never forthcoming.

Deciding on a Development Model

As I said above, I didn't presume Runrig's model of development would be the ideal fit for Farm Flow's stated aims, at least not before a careful evaluation. Given Matthew's previous track record with third-party developers, I wanted to take special care to recommend a development model that best suited his goals, even if I turned out not to be the best contractor for the job. At the time, funding was provided by Mad Agriculture, an organization that supports regenerative agriculture and cooperative models of land management and financing. Both they and Matthew wanted to ensure that the project remained farmer-owned and controlled. Matthew also sought to earn some additional revenue from the project, so long as it didn't become a second or third fulltime job; running a farm is already two fulltime jobs, at least, and Matthew decidedly wanted to keep farming. On my end, I made clear that I only do work by contract if it is licensed as free and open source software, preferably the GNU Affero General Public License (AGPL). Other prospective funding partners also expressed interest in the project being free and open source.

Under most standard development models, retaining ownership and control of the software will incur at least one of the following two expenses:

- Lots of your own time and expertise to design and engineer the software yourself, or

- Lots of money to pay someone else to do it for you.

More often than not, it's some combination of the two, with the money coming from venture capital and the expertise coming from overworked startup employees who've been promised a share in the future equity. If you want to recoup any of those costs, let alone if you'd like there to be some sizeable equity leftover for anyone once all those liabilities have been paid down, you may be inclined to reach for two additional mechanisms to guarantee a stable revenue stream:

- A proprietary license on at least some portion of the source code, plus

- A reliable means of securing that source code so it cannot be illicitly copied or reverse engineered.

The necessary security can be achieved by running the proprietary code behind a server that users cannot access directly, or by compiling the code to a binary format before distributing it, plus some digital rights management (DRM) software mixed in for good measure. There are other ways, but those are the most common. Users can subscribe to the service in the former case, or purchase a license and install the binaries in the latter, but either way, they will never see the source code, let alone be able to modify it.

At a glance, a subscription model may seem like the most feasible means of yielding revenue from a software project, particularly one that includes some sort of web-based server. A proprietary license is not essential to such a model, because even if users can self-host a server that's licensed as free software, few of them will actually want to. Selling managed hosting or support has been a viable means of driving a profit for open source software since Red Hat and WordPress pioneered the strategy over two decades ago. A free license, however, will naturally limit your margins, since someone is pretty sure to offer a competing service if you get too greedy and start charging subscription rates too far in excess of the costs of providing that service.

A proprietary license eliminates that ceiling, at least in theory. Red Hat and WordPress remain profitable, but only because they're able to work within those margins. Support services are the entirety of their business model and open source is their key selling point. It's harder to imagine a significant revenue stream for open source support if you're not providing that support fulltime. You can hire engineers to do the lion's share of the work for you, but still, the margins are essentially capped. Again, if you overcharge for subscriptions or under-compensate your workers to maintain the service, you could end up with your workers or customers being poached, if not outright revolt on all fronts. Either way, your fulltime job will most assuredly become that of a product manager, just to have a fighting chance of keeping the margins viable and the pitchforks at bay.[2]

All the same, I made the case that even with a proprietary license, an outsized contribution of Matthew's own time and money would be necessary to preserve the level of ownership and control he wanted. So although it would probably never be the source of passive income he hoped for, I recommended that a fully free – i.e., "copyleft" – license like the AGPL was still his best bet for getting the most value from the software while still retaining control of its development.

The Case for Free Software

In any software project, the more components you have to build from scratch the more time and money you'll need to invest just to reach parity with competing applications in terms of basic functionality and feature richness. Right off the bat, this will divert resources away from implementing the unique features that represent you core value proposition. Furthermore, that doesn't begin to account for the long-term cost of maintenance, which will be even higher for proprietary portions of the code, since you'll have to cover that cost entirely on your own. Throw in marketing and other overhead costs and you can see where that can quickly outstrip the budget for a small, community-driven software project.

As a proprietary project, you're a small fish in a big pond left to fend for yourself. You're up against the vast resources of Silicon Valley and it becomes an uphill battle just to break even. If you create a distinct product lucrative enough to compete, venture capital will eventually get wise to what you're selling and want a piece. That'll happen as soon as you start earning any kind of profit worthy of notice, especially if that entails taking away a share of their users. Unless you're ready to go toe-to-toe, pound-for-pound with Big Tech, you run the risk of being out-gunned, undercut, and bought out, all in quick succession. At that point, you've wound up exactly in the same predicament you originally intended to avoid: someone else owns your IP (or the knock-off version that just put you out of business), and now you're just another paying subscriber – take it or leave it. Maybe you accept VC investment yourself, giving you enough of an edge to survive or cash out while you're still ahead; however, that more or less amounts to the same loss of control, unless you're incredibly shrewd, and even then, it means you probably haven't sat on a tractor in a very long time.

As a free software project – or more to the point, as a part of a free software community – you can potentially start way out in front of where you'd be if you had gone the proprietary route. At the risk of sugarcoating it a bit, it's like everyone is first to market, because everyone gets to use each other's stuff and improve on each other's efforts. There's still a ton of hard work required and plenty of caveats to doing it right, but if you're willing to really lean into the cooperative process and engage with the larger community, the rewards can be manifold.

From a purely economical perspective, you've drastically reduced the amount of time and money you need for up front feature parity, as well as long-term maintenance. Of course, a lot of boilerplate code is open source and not copyleft, so those tools and components would be available to proprietary projects, too, not just other free and open source projects. But this is where leaning into a fully free software development model, with a copyleft license like the GPL or AGPL, can really start to pay off. To start off, you gain access to additional free software as an eligible licensee for those components that are also copyleft. The most critical part, however, comes from thinking not only in terms of simple economic benefits – though don't get me wrong, I'm not ruling those out either! – but rather in terms of the community's total social, political, and ecological benefits, which are no less tangible and can have far greater impact.

The GNU Affero General Public License is a free software license that ensures everyone can use the software however they see fit, so long as any derivative works they create can also be used freely by everyone else. This is intended to create a virtuous cycle that perpetually enriches the software commons. It is a commitment that all contributors make to one another: namely, that they will seek to build on each other's work and cooperate for the mutual benefit of all, rather than competing against each other, keeping their work siloed, and reduplicating each other's efforts in the process.

The AGPL also ensures every contributor that they will never be prohibited from later accessing their own contributions. As outlined above, this is an easy trap to fall into with proprietary software, even as its current owner, but this often goes overlooked. Luckily, as the developer of software licensed under the AGPL, the code that you author and deploy for one client is code you can offer to deploy, improve, and extend for your next client. As the sponsor of software licensed under the AGPL, you're free to hire someone else to audit, modify, or improve the software at any time, whether or not you or they were involved in its original development. Users who share their expertise on forums to help other users, or who volunteer their time to documenting and submitting bug reports and feature proposals, will never lose access to the software they worked to make better. By choosing to work together, contributing openly and freely to the same platform, they can all exercise greater control over the project’s direction. Collaboration and openness only amplifies each others efforts, it never diminishes it.

Initial Recommendations

After thorough discussion with Matthew on all of the preceding points, I summarized my initial recommendations for developing the Farm Flow application as follows:

- Prioritize the Farm Flow Board and the quickest pathway to developing an implementation that can be demonstrated with high fidelity, even without a supporting backend or network connectivity.

- Look for ready-to-use, third-party applications that can be adopted early on then later integrated with the Farm Flow Board, such as LiteFarm or farmOS. Keep development focused on Farm Flow’s core value proposition of the board and its other unique features.

- Assess interest from potential users and funders before deciding on a backend architecture to support the Farm Flow Board as it develops into a more robust dashboard and nerve center for the other core features.

- Distribute the costs of ownership and control over development; rather than scaling a product, think in terms of organizing support and strategic reach.

See the Farm Flow Pilot and final Farm Flow Development Strategy for more information on how the project proceeded.

The first time I ever tried to fully explain Runrig to anyone else was on a short hike with Samuel on the last day of GOAT 2022. The last in a series of momentous conversations, it came at the precise moment when Runrig started taking definite shape in my own mind, and I attribute much of Runrig's essential characteristics to Sam's astute guidance and constructive feedback. ↩︎

Not to put too fine a point on it, but I summed this up by telling Matthew that it would be hard to create a source of passive income out of Farm Flow without one of us exploiting the other. There's a long history of rentier relations in both agriculture and technology. In agriculture it is called feudalism. More recently, Yanis Varoufakis has made a compelling case that we are entering a new era of what he calls Technofeudalism. ↩︎